Land cover

Type of resources

Available actions

Topics

Keywords

Contact for the resource

Provided by

Years

Formats

Representation types

Update frequencies

status

-

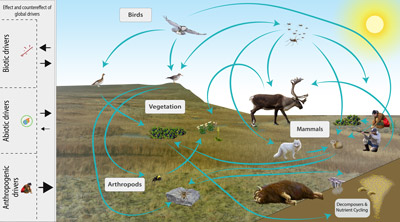

The Arctic terrestrial food web includes the exchange of energy and nutrients. Arrows to and from the driver boxes indicate the relative effect and counter effect of different types of drivers on the ecosystem. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 2 - Page 26- Figure 2.4

-

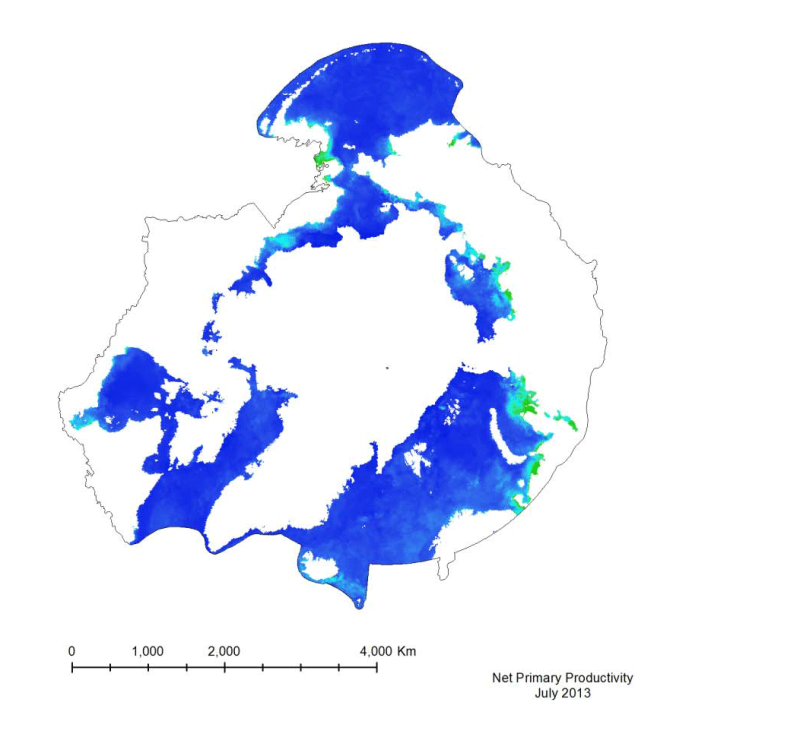

Marine primary productivity is not available from the NASA Ocean Color website. Currently the best product available for marine primary productivity is available through Oregon State University’s Ocean Productivity Project. A monthly global Net Primary Productivity product at 9 km spatial resolution has been selected for this analysis. The algorithm used to create the primary productivity is a Vertically Generalized Production Model (VGPM) created by Behrenfeld and Falkowski (1997). It is a “chlorophyll-based” model that estimates net primary production from chlorophyll using a temperature-dependent description of chlorophyll photosynthetic efficiency (O’Malley 2010). Inputs to the function are chlorophyll, available light, and photosynthetic efficiency.

-

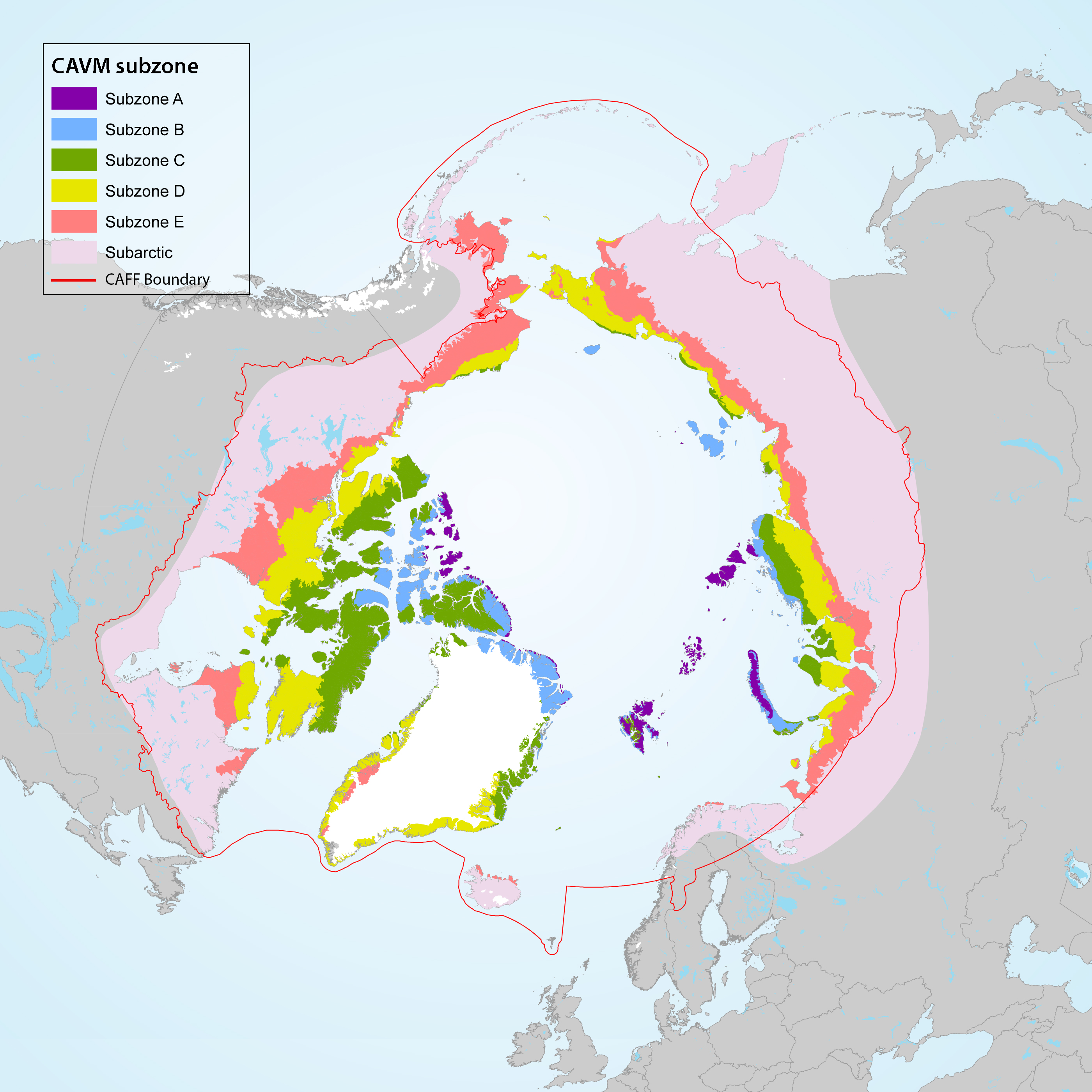

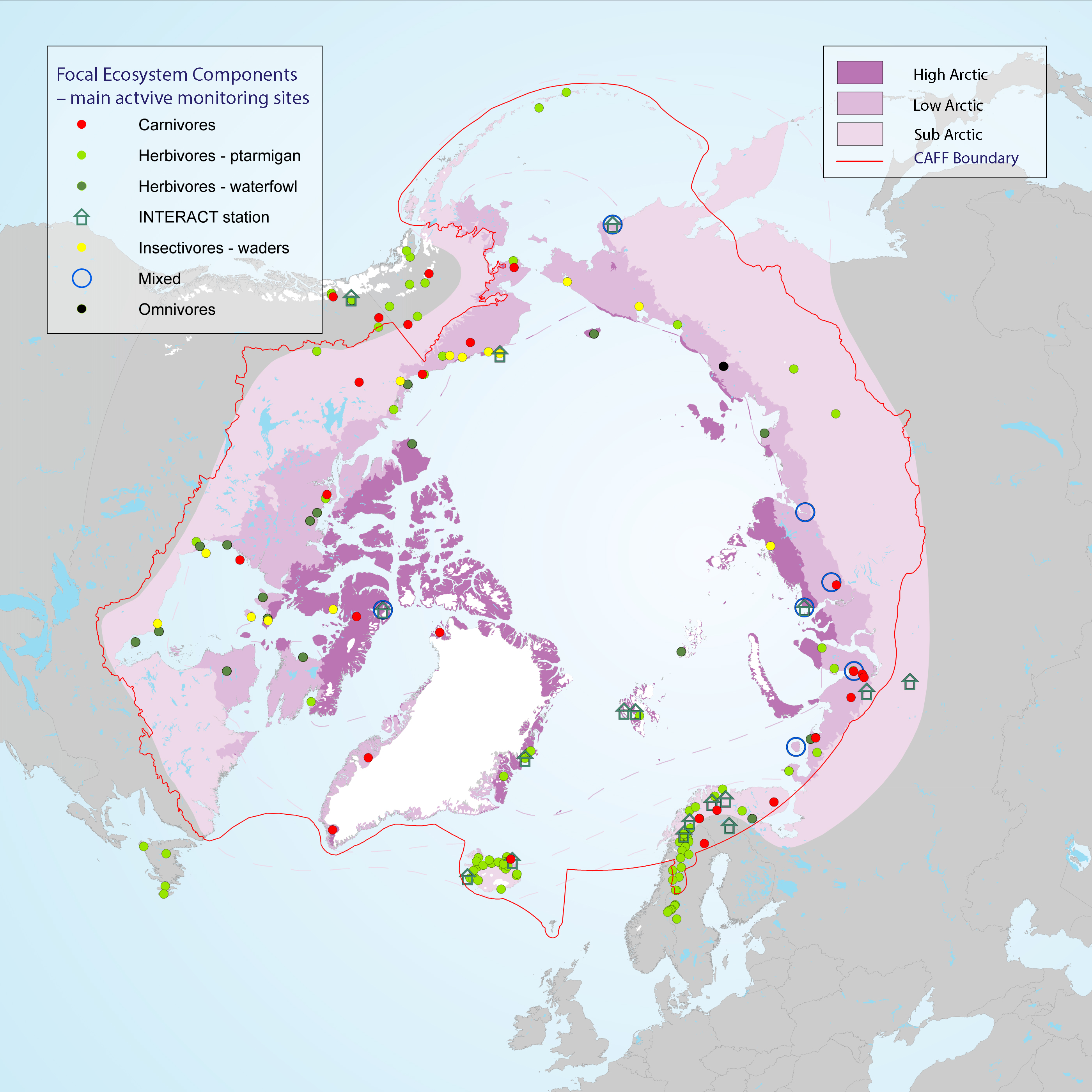

Geographic area covered by the Arctic Biodiversity Assessment and the CBMP–Terrestrial Plan. Subzones A to E are depicted as defined in the Circumpolar Arctic Vegetation Map (CAVM Team 2003). Subzones A, B and C are the high Arctic while subzones D and E are the low Arctic. Definition of high Arctic, low Arctic, and sub-Arctic follow Hohn & Jaakkola 2010. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 1 - Page 14 - Figure 1.2

-

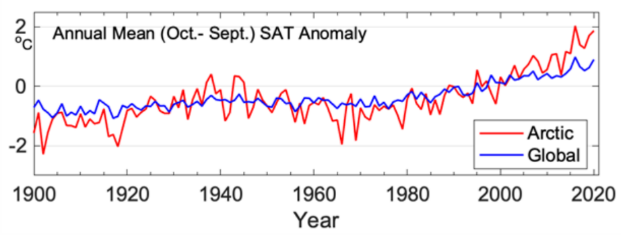

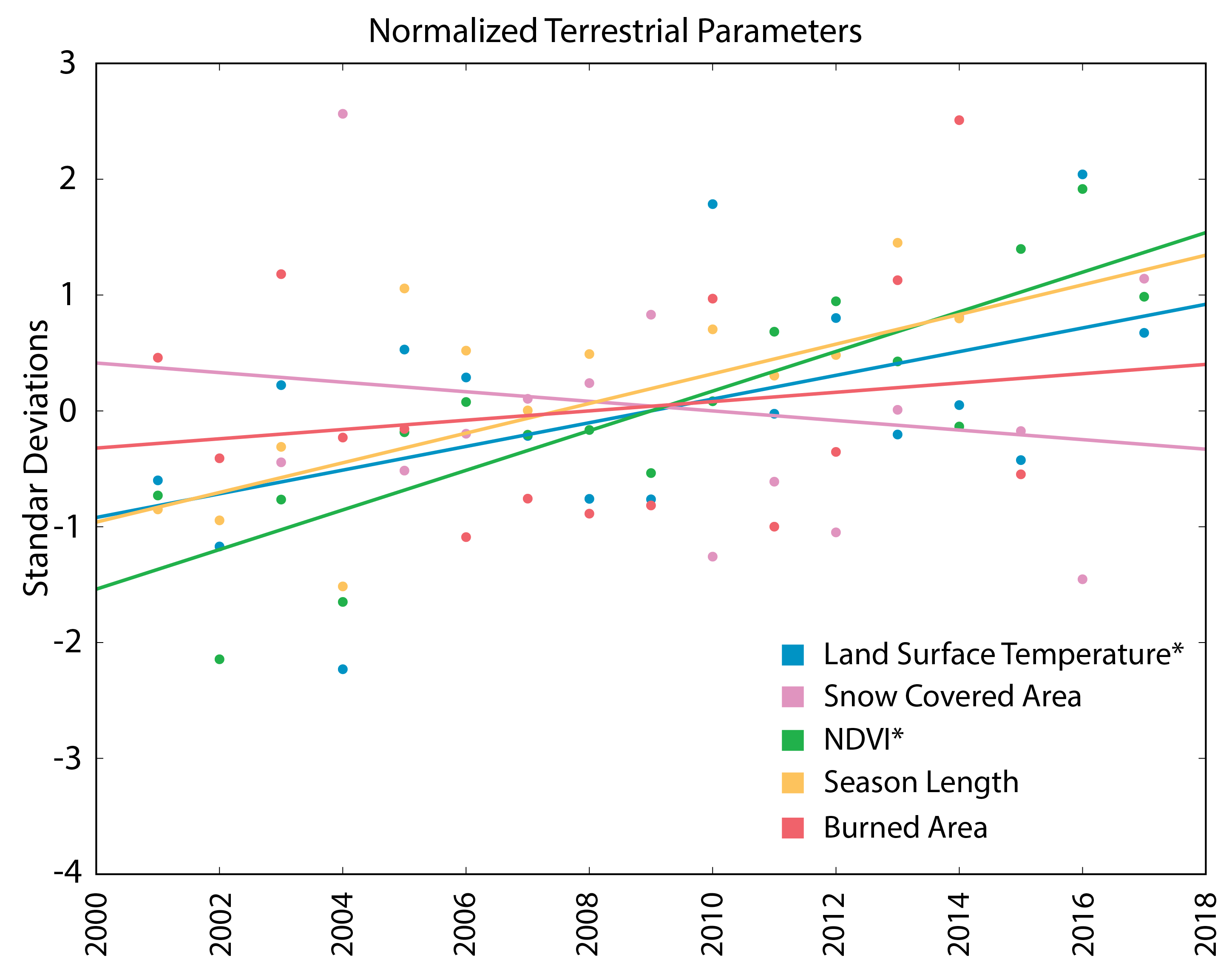

Warming in the Arctic has been significantly faster than anywhere else on Earth (Ballinger et al. 2020). Trends in land surface temperature are shown on Figure 2-2. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 2 - Page 23 - Figure 2.2

-

Many population counts of gregarious migrant species, such as waders and geese, take place along the flyways and at wintering grounds outside the Arctic which stresses the importance of continued development of movement ecology studies. Monitoring of FEC attributes related to breeding success and links to environmental drivers within the Arctic takes place in a wide network of research sites across the Arctic, although with low coverage of the high Arctic zone (Figure 3-25) STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 58 - Figure 3.25

-

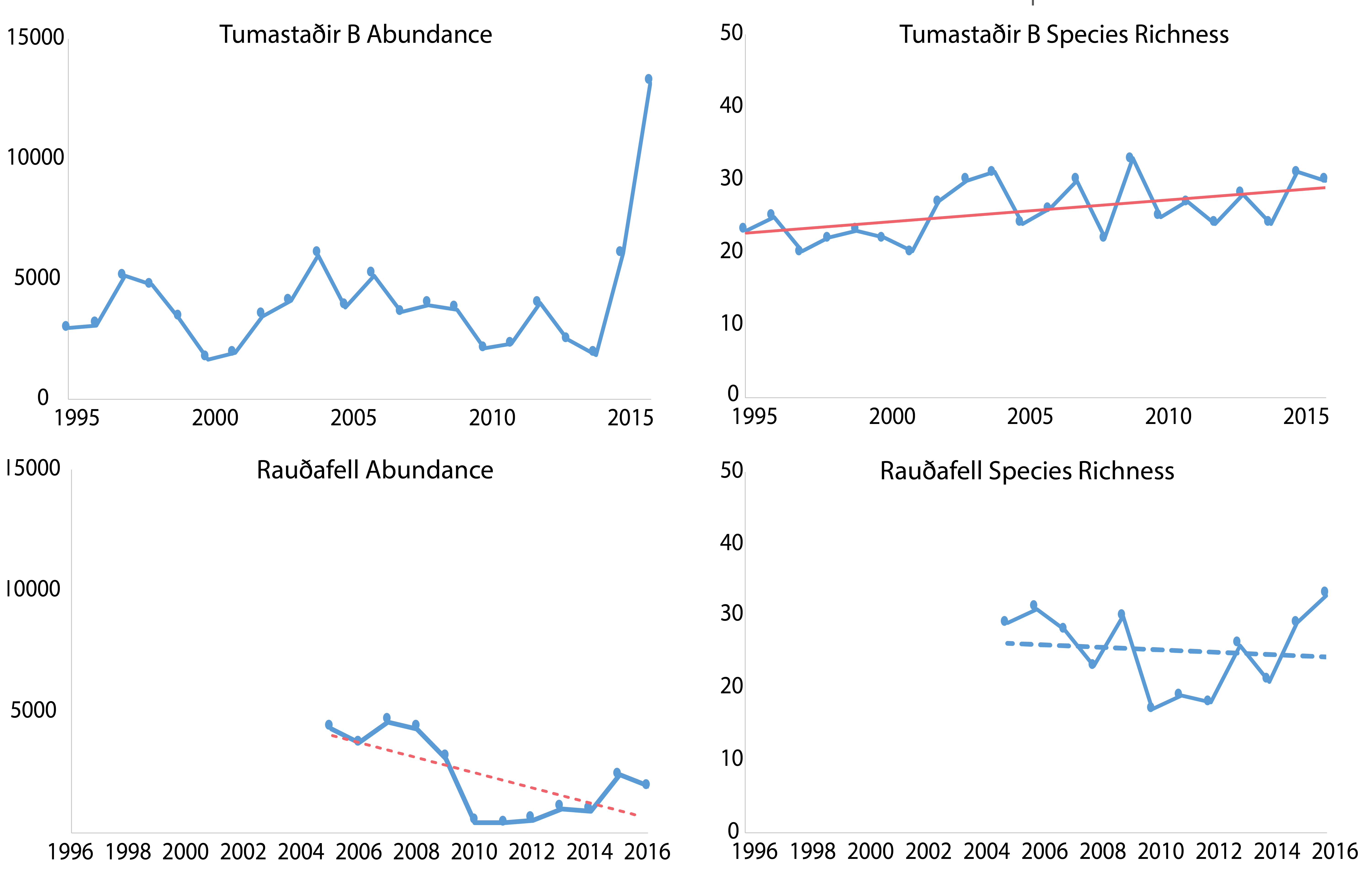

Trends in total abundance of moths and species richness, from two locations in Iceland, 1995–2016. Trends differ between locations. The solid and dashed straight lines represent linear regression lines which are significant or non-significant, respectively. Modified from Gillespie et al. 2020a. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 41 - Figure 3.14

-

Rates of change among different terrestrial parameters, using average annual standardised data for the pan-Arctic. *identifies parameters with statistically significant trends. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 95 - Figure 3.33

-

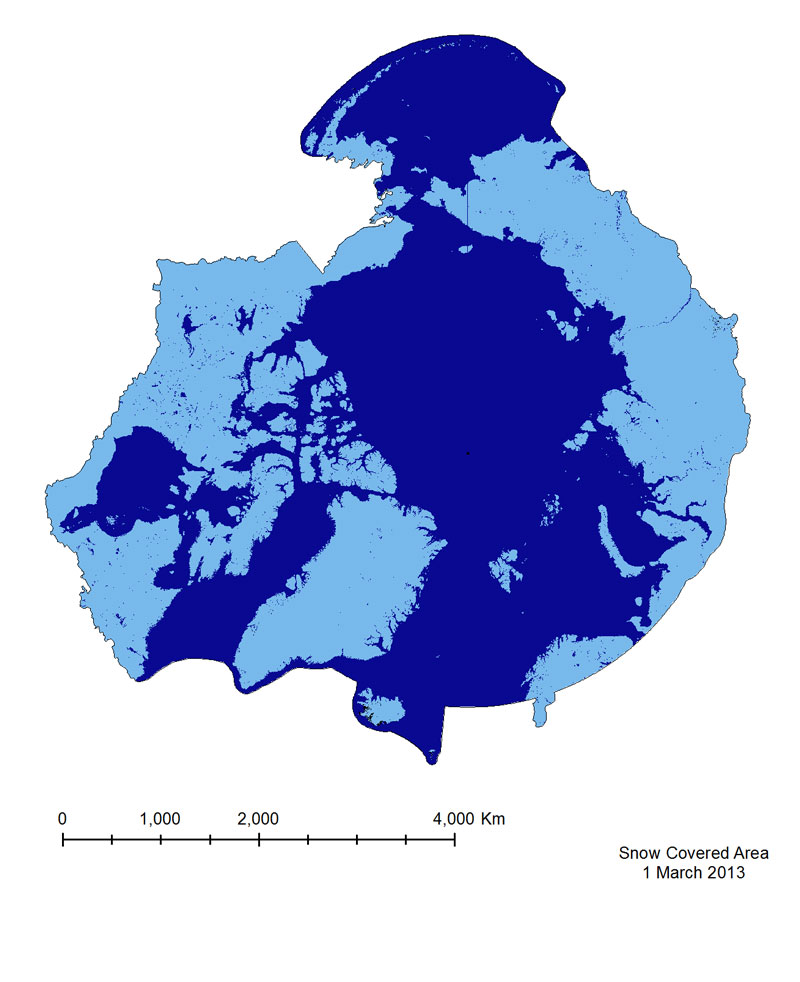

The Snow Covered Area product is based on a Normalized Difference Snow Index(NDSI), which is similar to NDVI, but exploits different bands in the equation (Equation 3),namely Green (Band 4) and Short Wavelength Near-infrared (SWNIR, Band 6). It isimportant to note that the Band 6 sensor on MODIS Aqua malfunctioned shortly after launch,so Snow Covered Area from the Aqua sensor is calculated using Bands 3 and 7. This mayintroduce errors in identifying snow in vegetated areas, as the use of Band 7 results in falsesnow detection. For this reason the MODIS Terra product has been provided for the CAFF-system.

-

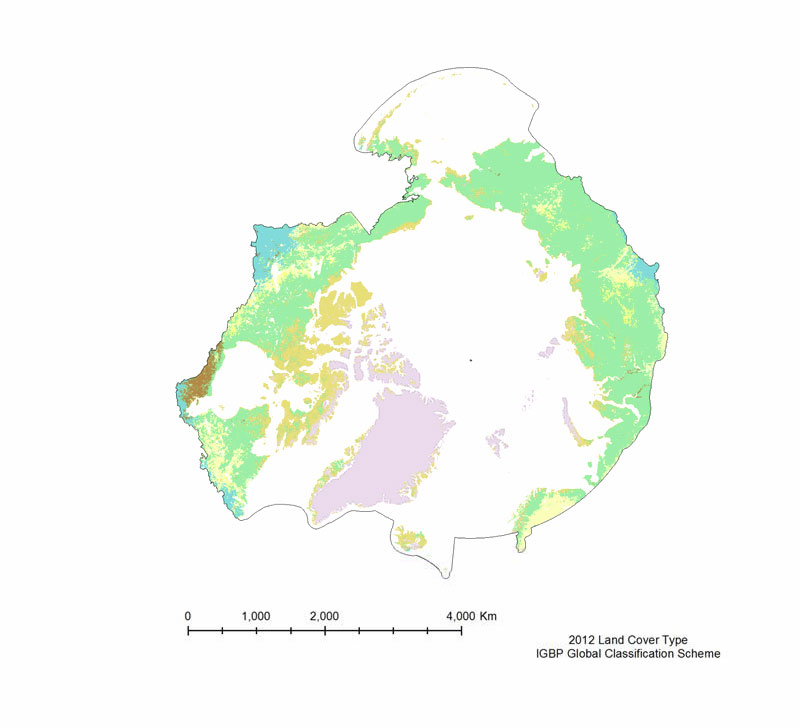

The MODIS Land Cover Type product is created yearly using three landclassification schemes; the International Geosphere Biosphere Programme (IGBP)classification scheme, the Univertiy of Maryland (UMD) classification scheme, and aMODIS-derived Leaf Area Index /Fraction of Photosynthetically Active Radiation(LAI/fPAR) classification scheme (Table 3). The International Geosphere Biosphere Programme (IGBP) identifies seventeenland cover classes, including eleven natural vegetation classes, three non-vegetated landclasses, and three developed land classes. The product provided is derived using the samealgorithm as the 500 m Land Cover Type (MOD12Q1), but is on a 0.05° Climate Model Grid(CMG), that has been clipped to the pan-Arctic extent. The UMD classification scheme issimilar to the IGBP classification scheme, but it excludes the Permanent wetlands,Cropland/Natural vegetation mosaic, and the Snow and ice classes. The LAI/fPARclassification scheme is the smallest of the three, and focuses on forest structure; it only haseleven classes. All three land cover classification schemes are provided, but the IGBPclassification scheme is the most amenable to the Pan-Arctic region.

-

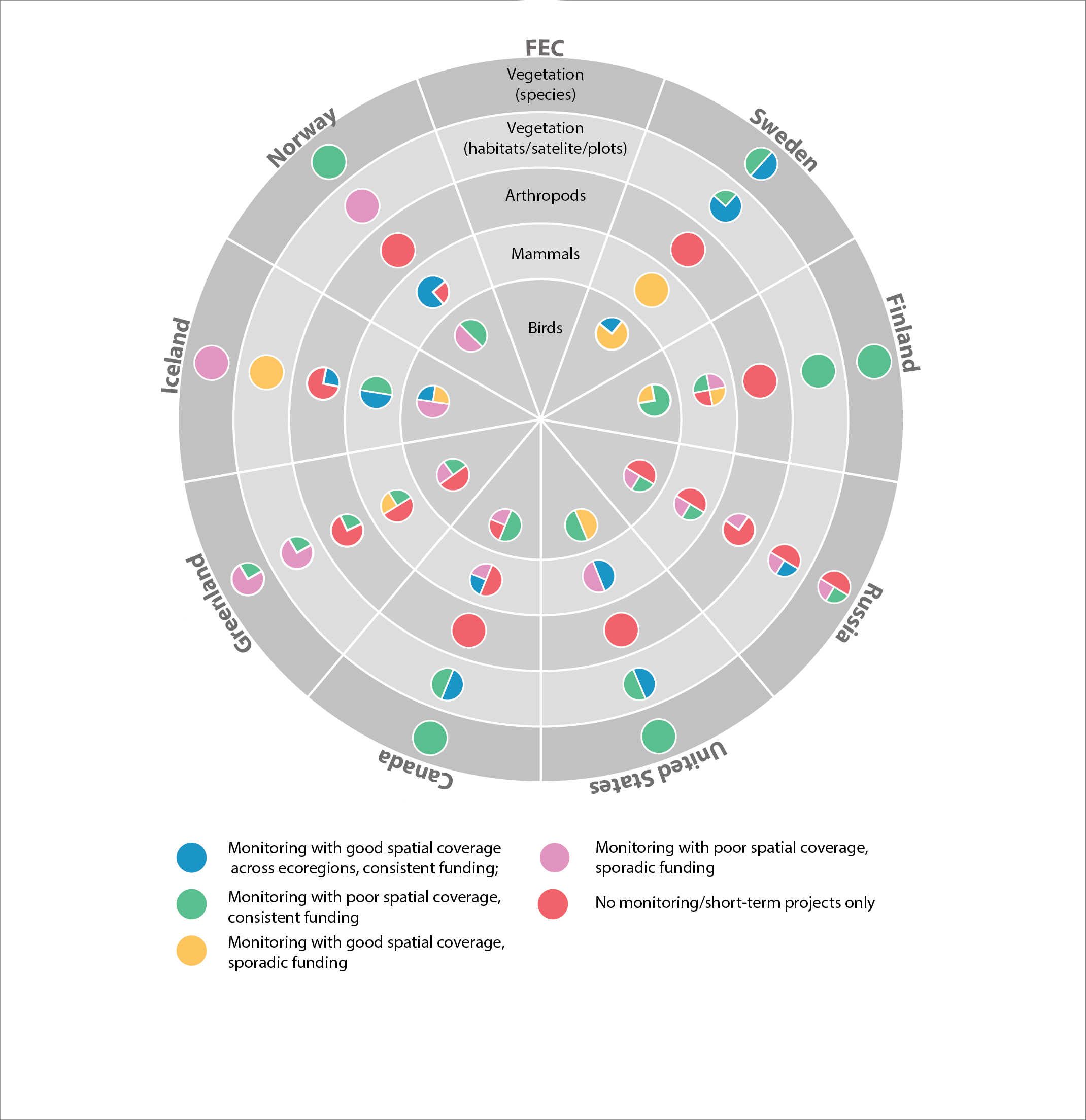

Current state of monitoring for Arctic terrestrial biodiversity FECs in each Arctic state. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 4 - Page 102 - Figure 4.1

CAFF - Arctic Biodiversity Data Service (ABDS)

CAFF - Arctic Biodiversity Data Service (ABDS)