Land use

Type of resources

Available actions

Topics

Keywords

Contact for the resource

Provided by

Years

Representation types

Update frequencies

status

-

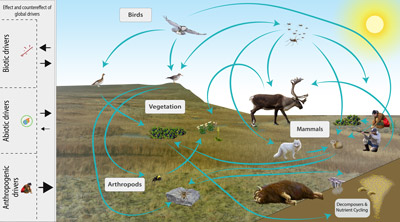

The Arctic terrestrial food web includes the exchange of energy and nutrients. Arrows to and from the driver boxes indicate the relative effect and counter effect of different types of drivers on the ecosystem. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 2 - Page 26- Figure 2.4

-

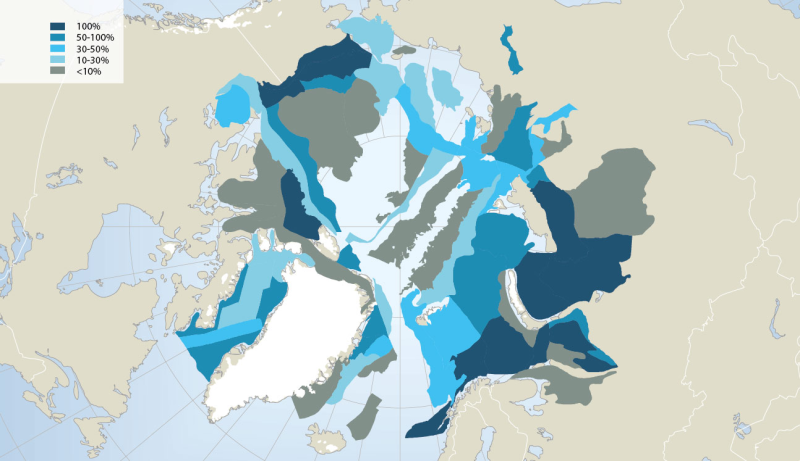

Extensive oil and gas activity has occurred in the Arctic, primarily land-based, with Russia extracting 80% of the oil and 99% of the gas to date (AMAP 2008). Furthermore, the Arctic still contains large petroleum hydrocarbon reserves and potentially holds one fifth of the world’s yet undiscovered resources, according to the US Geological Survey (USGS 2008) (Fig. 14.4). While much of the currently known Arctic oil and gas reserves are in Russia (75% of oil and 90% of gas; AMAP 2008), more than half of the estimated undiscovered Arctic oil reserves are in Alaska (offshore and onshore), the Amerasian Basin (offshore north of the Beaufort Sea) and in W and E Greenland (offshore). More than 70% of the Arctic undiscovered natural gas is estimated to be located in the W Siberian Basin (Yamal Peninsula and offshore in the Kara Sea), the E Barents Basin and in Alaska (offshore and onshore) (AMSA 2009). Associated with future exploration and development, each of these regions would require vastly expanded Arctic marine operations, and several regions such as offshore Greenland would require fully developed Arctic marine transport systems to carry hydrocarbons to global markets. In this context, regions of high interest for economic development face cumulative environmental pressure from anthropogenic activities such as hydrocarbon exploitation locally, together with global changes associated with climatic and oceanographic trends. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, CAFF 2013 - Akureyri . Arctic Biodiversity Assessment. Status and Trends in Arctic biodiversity. - Marine ecosystems (Chapter 14 - page 501). Figure adapted from the USGS

-

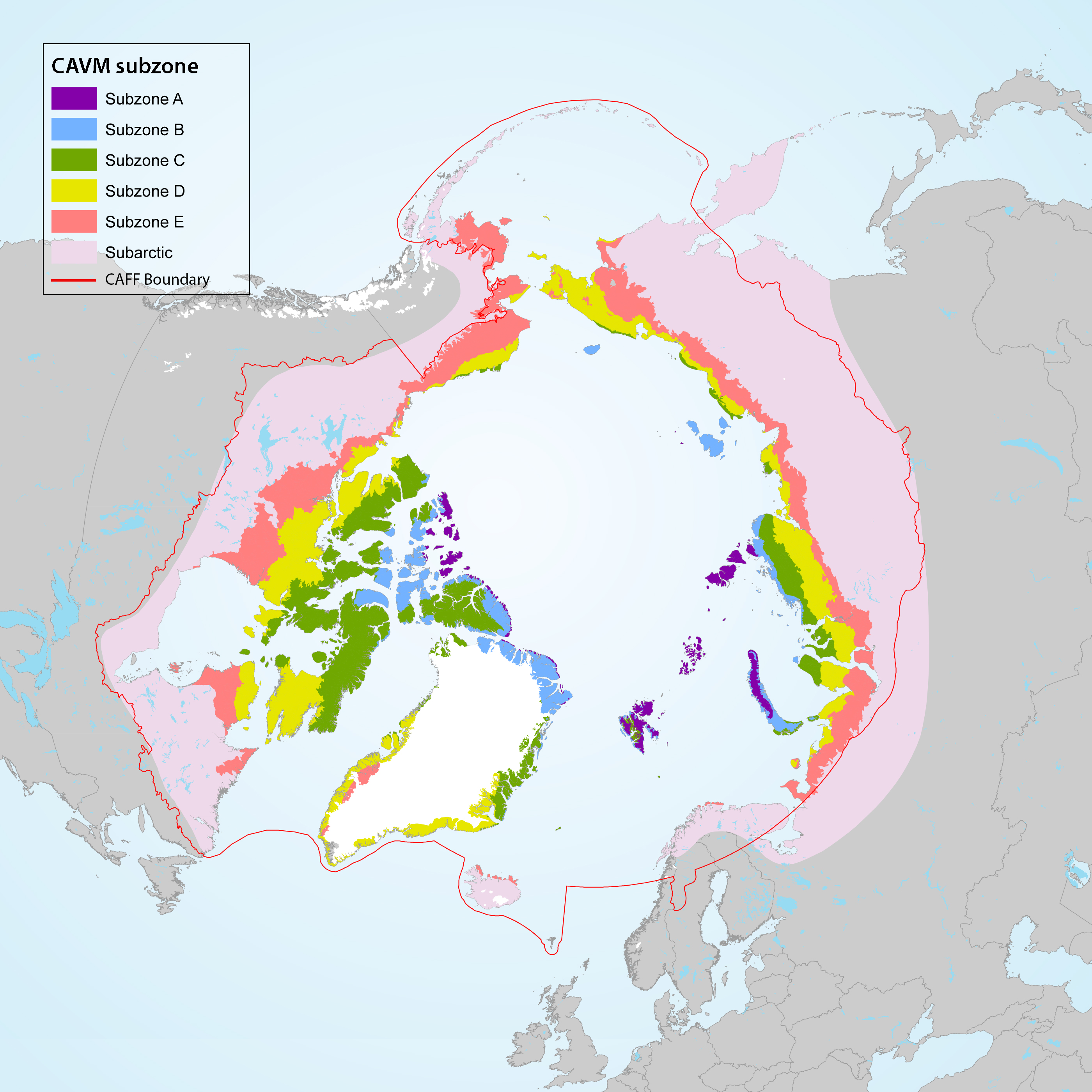

Geographic area covered by the Arctic Biodiversity Assessment and the CBMP–Terrestrial Plan. Subzones A to E are depicted as defined in the Circumpolar Arctic Vegetation Map (CAVM Team 2003). Subzones A, B and C are the high Arctic while subzones D and E are the low Arctic. Definition of high Arctic, low Arctic, and sub-Arctic follow Hohn & Jaakkola 2010. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 1 - Page 14 - Figure 1.2

-

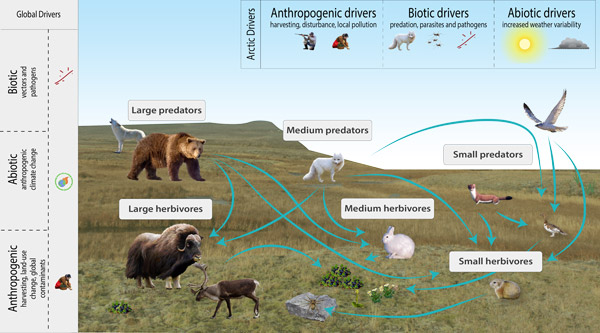

Conceptual model of Arctic terrestrial mammals, showing FECs, interactions with other biotic groups and examples of drivers and attributes relevant at various spatial scales. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 67 - Figure 3.28

-

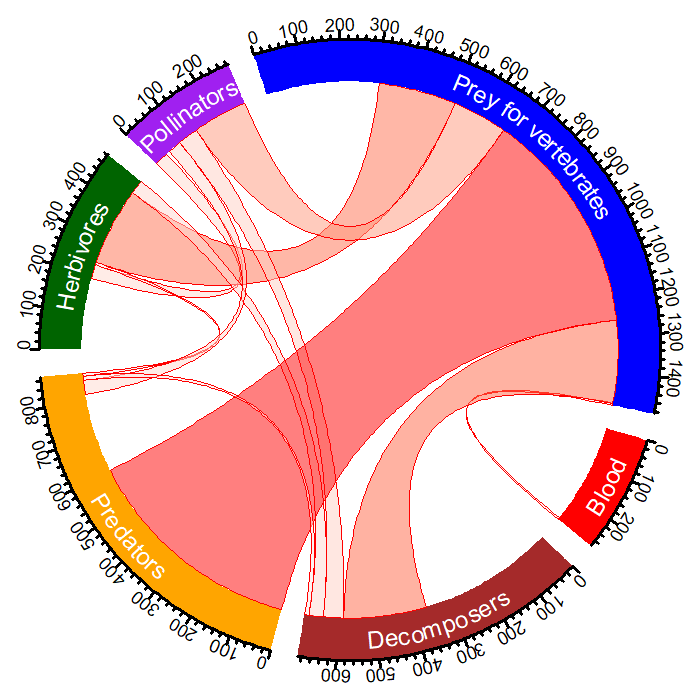

The diagram indicates the number of species in each FEC for the North Atlantic region of the Arctic (circular outline) and the overlap between the five CBMP–Terrestrial Plan FECs and the additional ‘predators’ FEC. The link width indicates the number of species linking two FECs. The larger the link the more species that are found in linking FECs. Modified from Gillespie et al. 2020a. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 38 - Figure 3.8

-

Arctic foxes are currently monitored at 34 sites throughout the North, with most monitoring efforts concentrated in Fennoscandia (Figure 3-32). The duration of monitoring across all sites is variable at between 2 and 56 years and was ongoing at 27 of the 34 sites (79%) as of 2015. Monitoring projects cover almost equally the four climate zones of the species’ distribution—high Arctic, low Arctic, sub-Arctic, and montane/alpine. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 82 - Figure 3.32

-

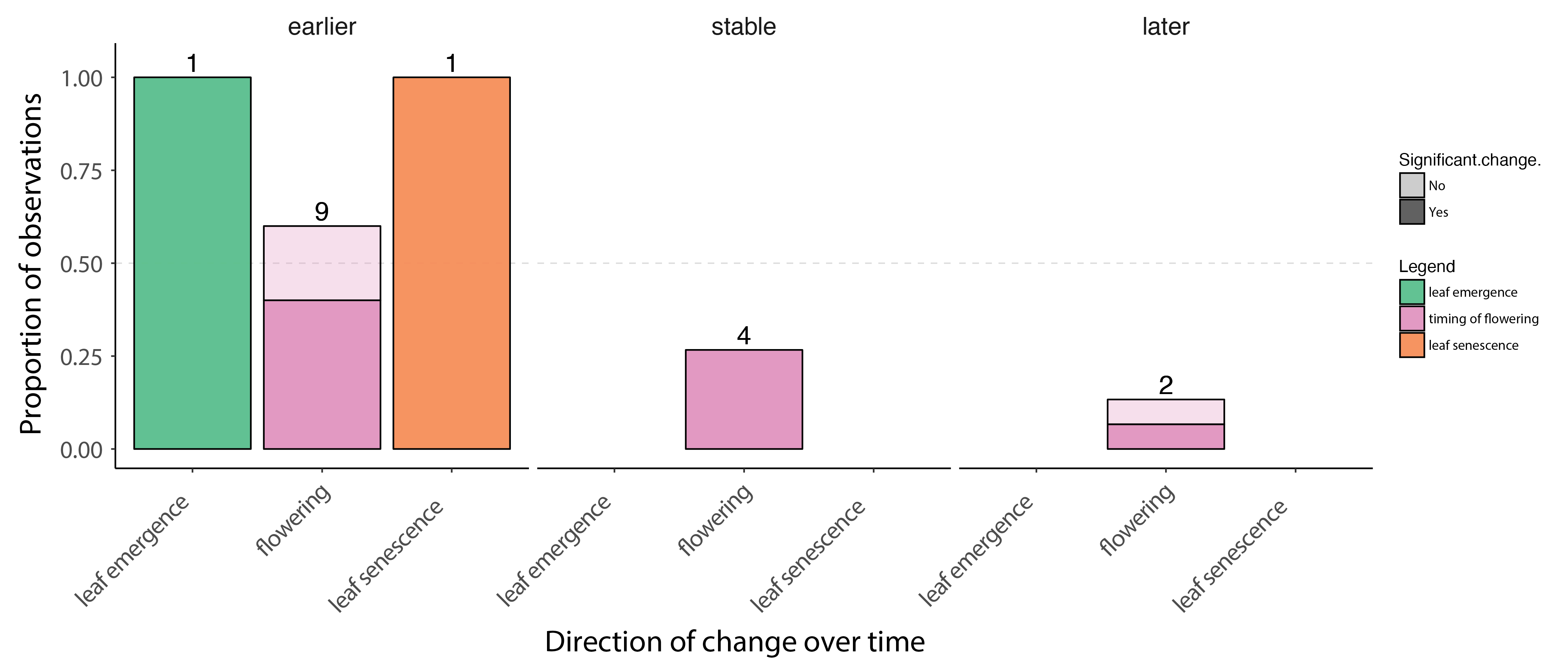

Change in plant phenology over time based on published studies, ranging from 9 to 21 years of duration. The bars show the proportion of observations where timing of phenological events advanced (earlier) was stable or were delayed (later) over time. The darker portions of each bar represent visible decrease, stable state, or increase results, and lighter portions represent marginally significant change. The numbers above each bar indicate the number of observations in that group. Figure from Bjorkman et al. 2020. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 31- Figure 3.3

-

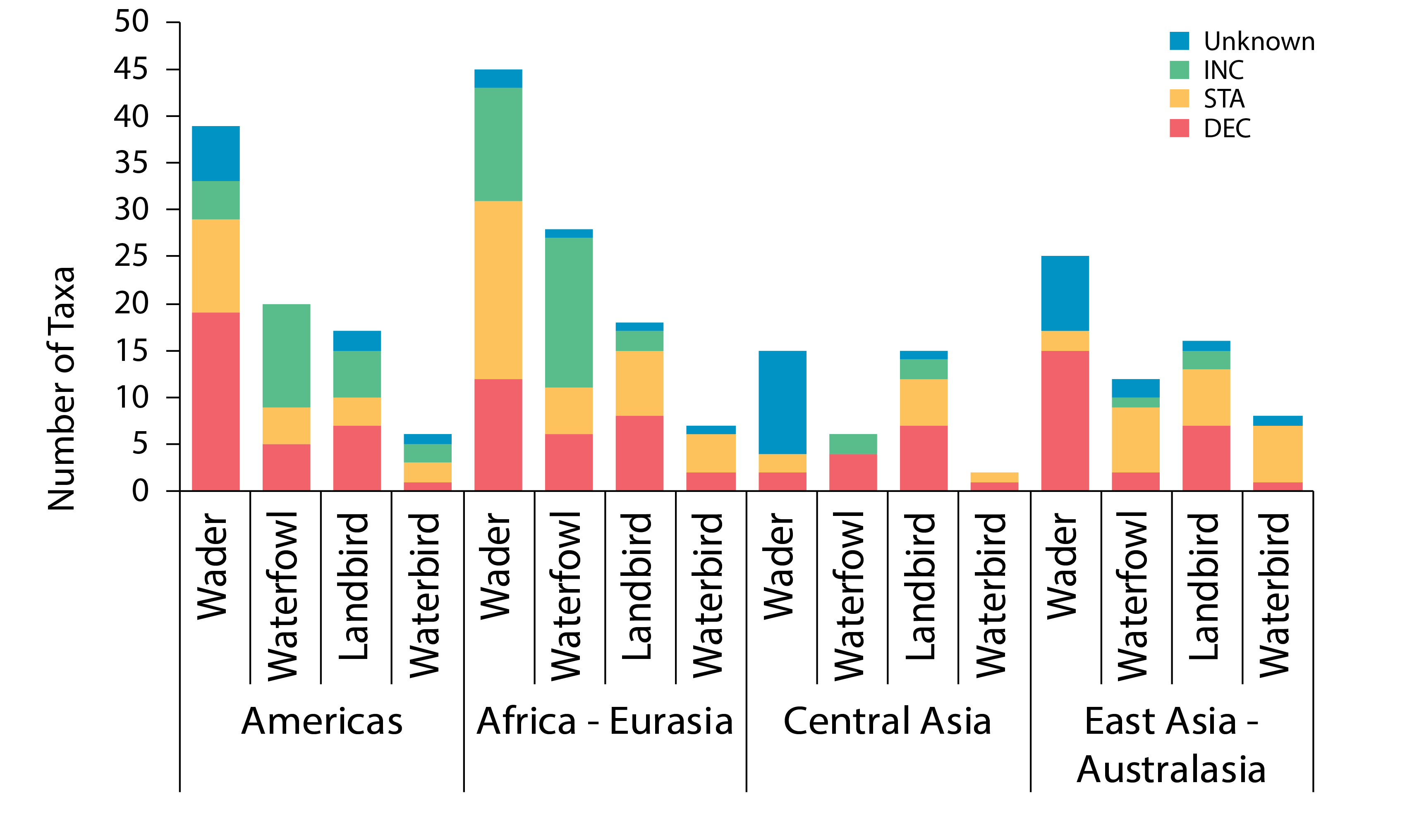

Trends in Arctic terrestrial bird population abundance for four taxonomic groupings in four global flyways. Data are presented as total number of taxa (species, subspecies). Modified from Smith et al. 2020. These broad patterns were generally consistent across flyways, with some exceptions. Fewer waterfowl populations increased in the Central Asian and East Asian–Australasian Flyways. The largest proportion of declining species was among the waders in all but the Central Asian Flyway where the trends of a large majority of waders are unknown. Although declines were more prevalent among waders than other taxonomic groups in both the African–Eurasian and Americas Flyways, the former had a substantially larger number of stable and increasing species than the latter (Figure 3-23). STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 55 - Figure 3.23

-

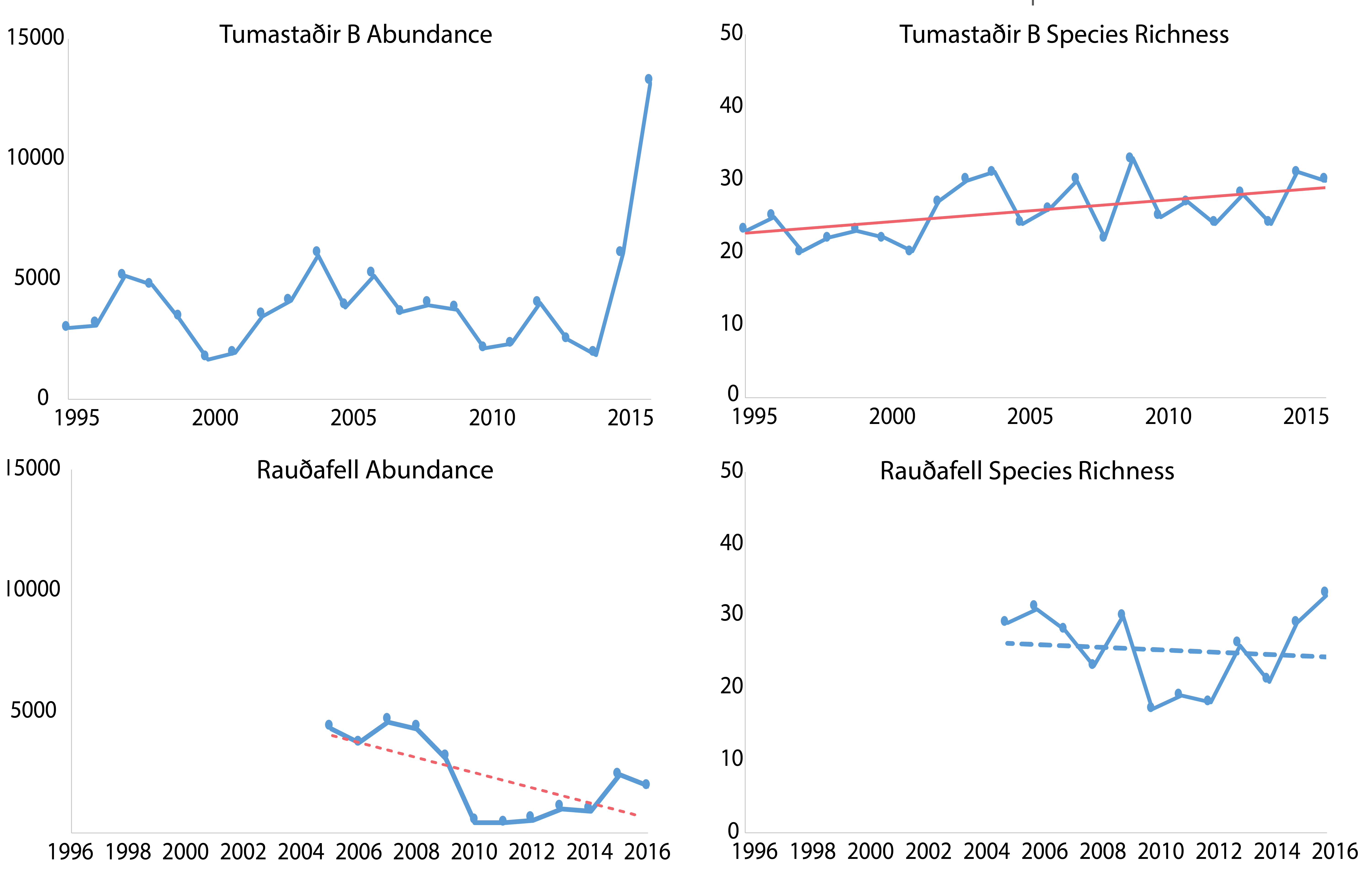

Trends in total abundance of moths and species richness, from two locations in Iceland, 1995–2016. Trends differ between locations. The solid and dashed straight lines represent linear regression lines which are significant or non-significant, respectively. Modified from Gillespie et al. 2020a. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 41 - Figure 3.14

-

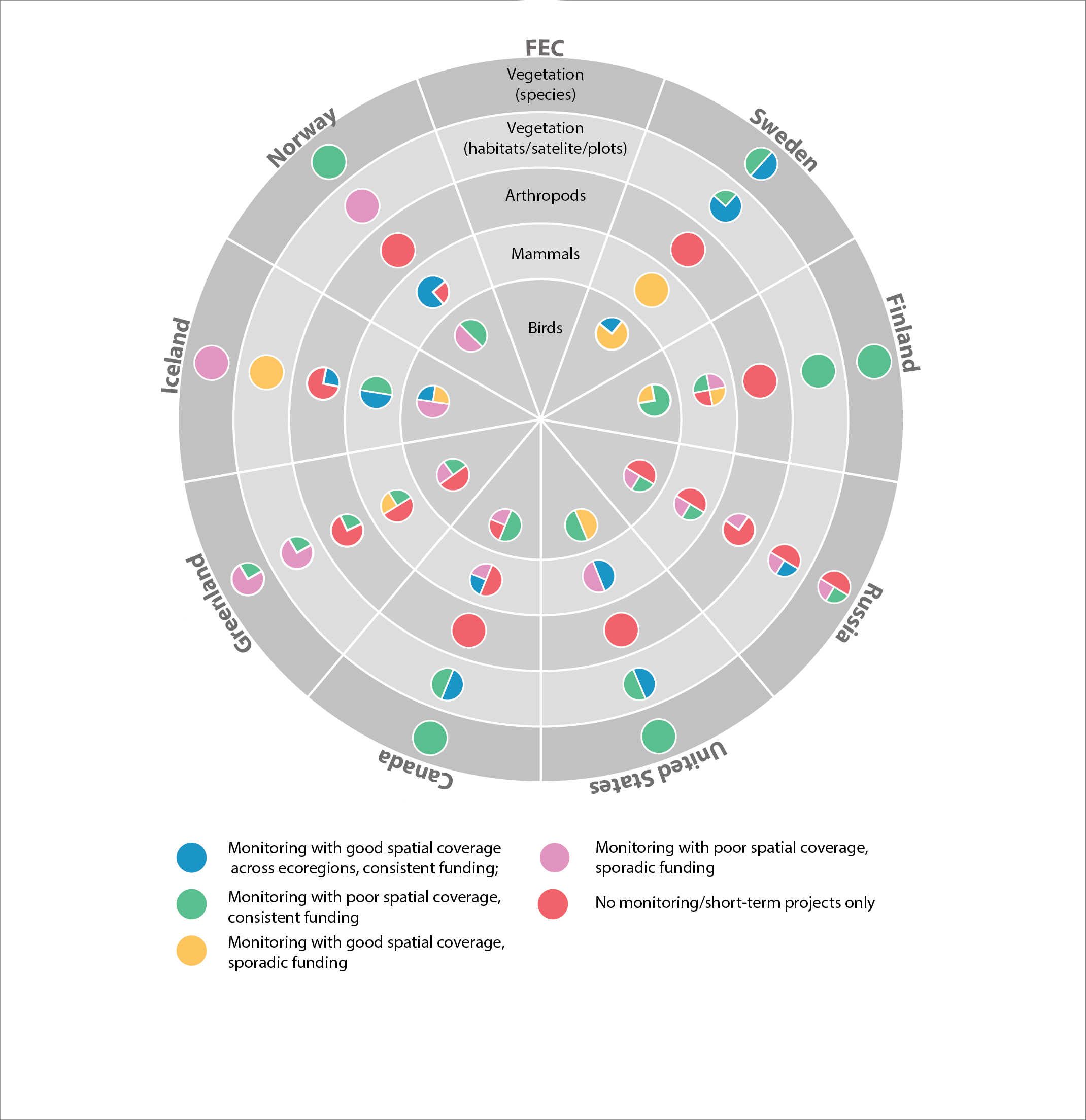

Current state of monitoring for Arctic terrestrial biodiversity FECs in each Arctic state. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 4 - Page 102 - Figure 4.1

CAFF - Arctic Biodiversity Data Service (ABDS)

CAFF - Arctic Biodiversity Data Service (ABDS)