Climatology, meteorology, atmosphere

Type of resources

Available actions

Topics

Keywords

Contact for the resource

Provided by

Representation types

Update frequencies

status

-

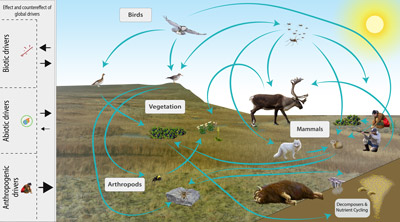

The Arctic terrestrial food web includes the exchange of energy and nutrients. Arrows to and from the driver boxes indicate the relative effect and counter effect of different types of drivers on the ecosystem. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 2 - Page 26- Figure 2.4

-

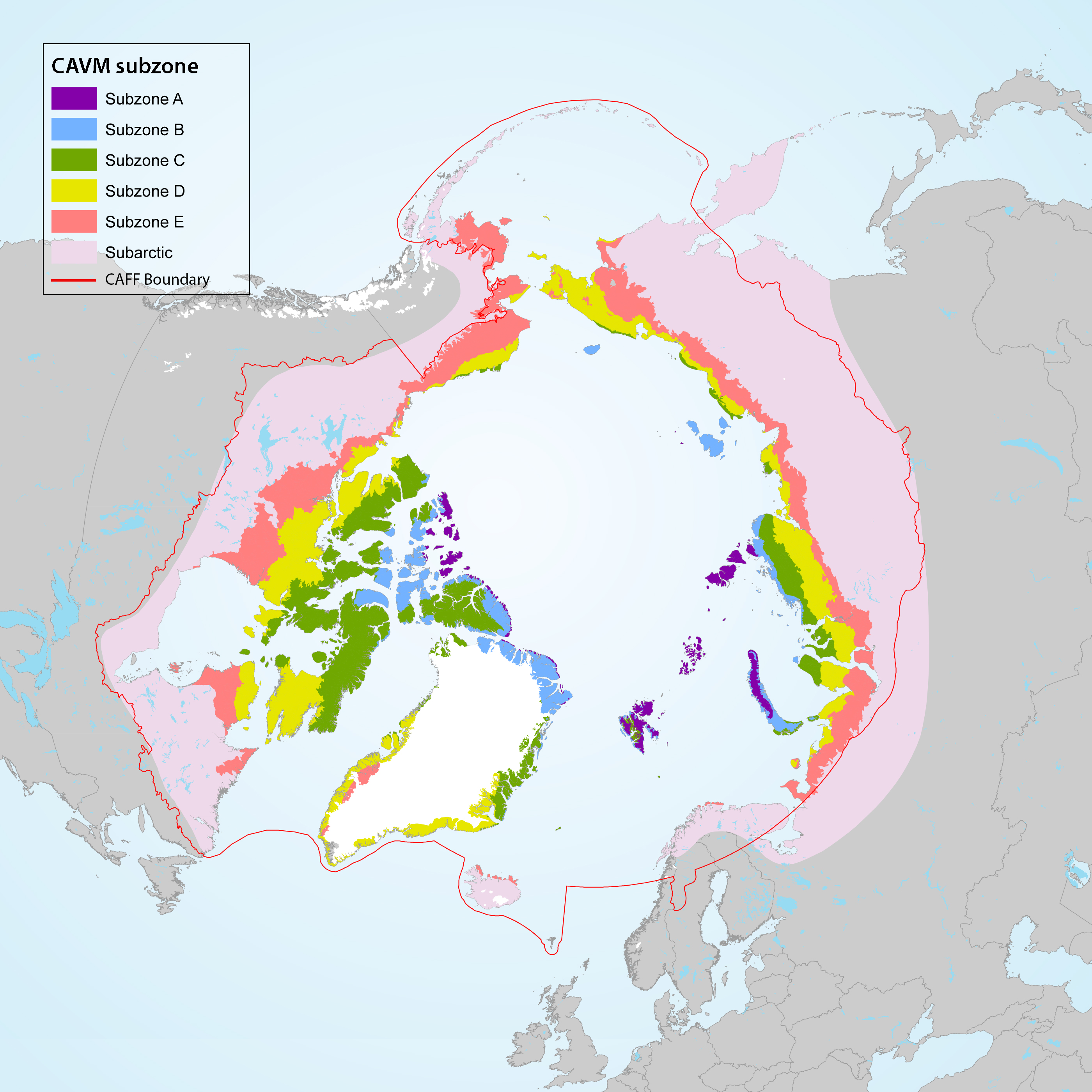

Geographic area covered by the Arctic Biodiversity Assessment and the CBMP–Terrestrial Plan. Subzones A to E are depicted as defined in the Circumpolar Arctic Vegetation Map (CAVM Team 2003). Subzones A, B and C are the high Arctic while subzones D and E are the low Arctic. Definition of high Arctic, low Arctic, and sub-Arctic follow Hohn & Jaakkola 2010. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 1 - Page 14 - Figure 1.2

-

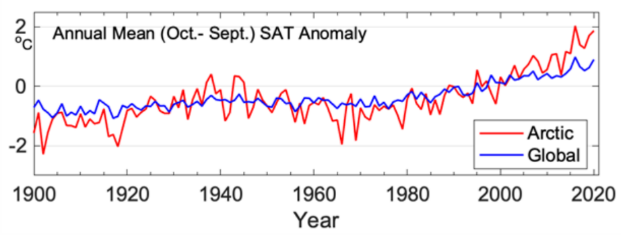

Warming in the Arctic has been significantly faster than anywhere else on Earth (Ballinger et al. 2020). Trends in land surface temperature are shown on Figure 2-2. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 2 - Page 23 - Figure 2.2

-

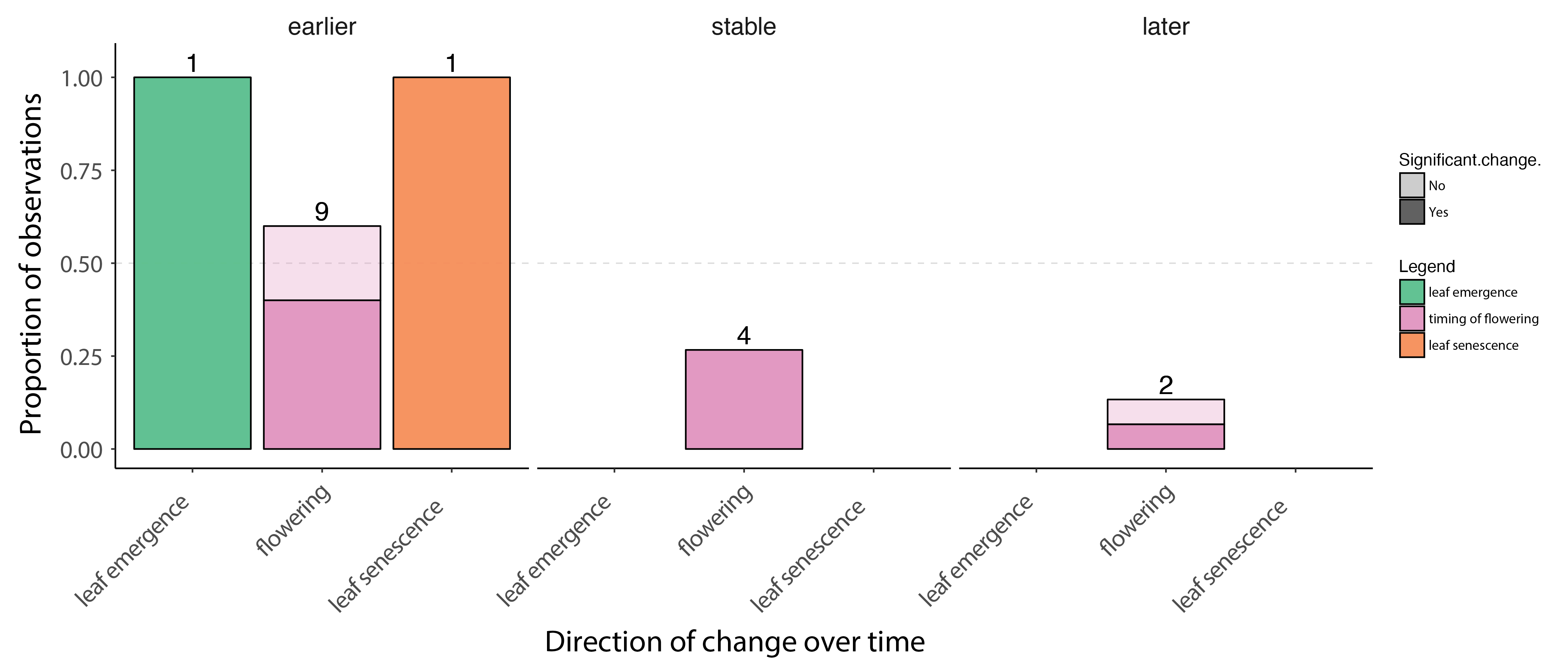

Change in plant phenology over time based on published studies, ranging from 9 to 21 years of duration. The bars show the proportion of observations where timing of phenological events advanced (earlier) was stable or were delayed (later) over time. The darker portions of each bar represent visible decrease, stable state, or increase results, and lighter portions represent marginally significant change. The numbers above each bar indicate the number of observations in that group. Figure from Bjorkman et al. 2020. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 31- Figure 3.3

-

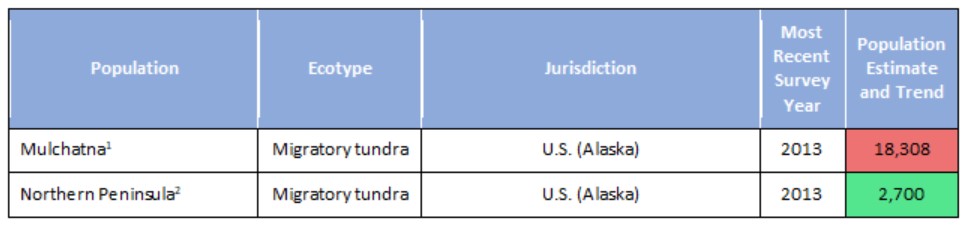

Population estimates and trends for Rangifer populations of the migratory tundra, Arctic island, mountain, and forest ecotypes where their circumpolar distribution intersects the CAFF boundary. Population trends (Increasing, Stable, Decreasing, or Unknown) are indicated by shading. Data sources for each population are indicated as footnotes. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 70 - Table 3.4

-

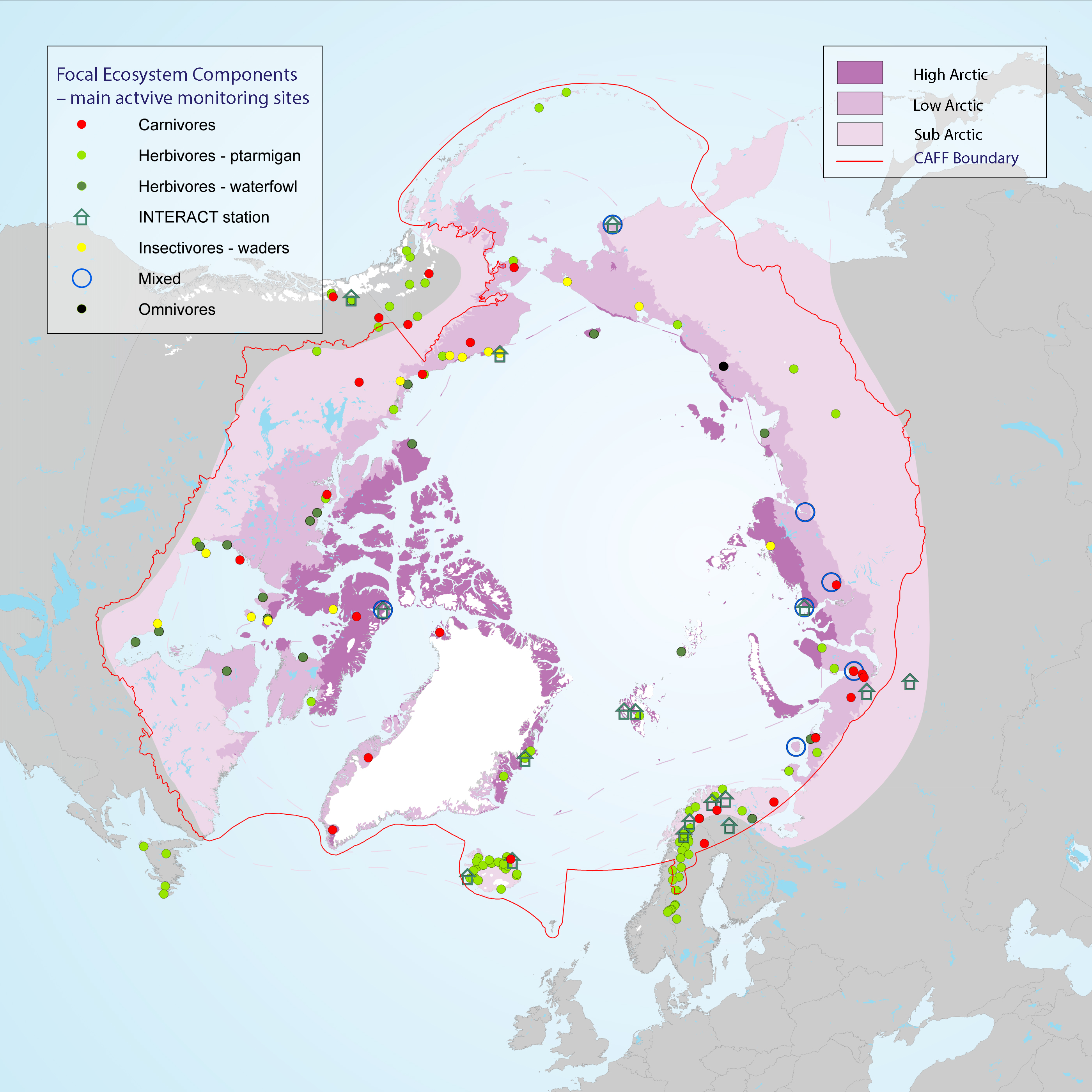

Many population counts of gregarious migrant species, such as waders and geese, take place along the flyways and at wintering grounds outside the Arctic which stresses the importance of continued development of movement ecology studies. Monitoring of FEC attributes related to breeding success and links to environmental drivers within the Arctic takes place in a wide network of research sites across the Arctic, although with low coverage of the high Arctic zone (Figure 3-25) STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 58 - Figure 3.25

-

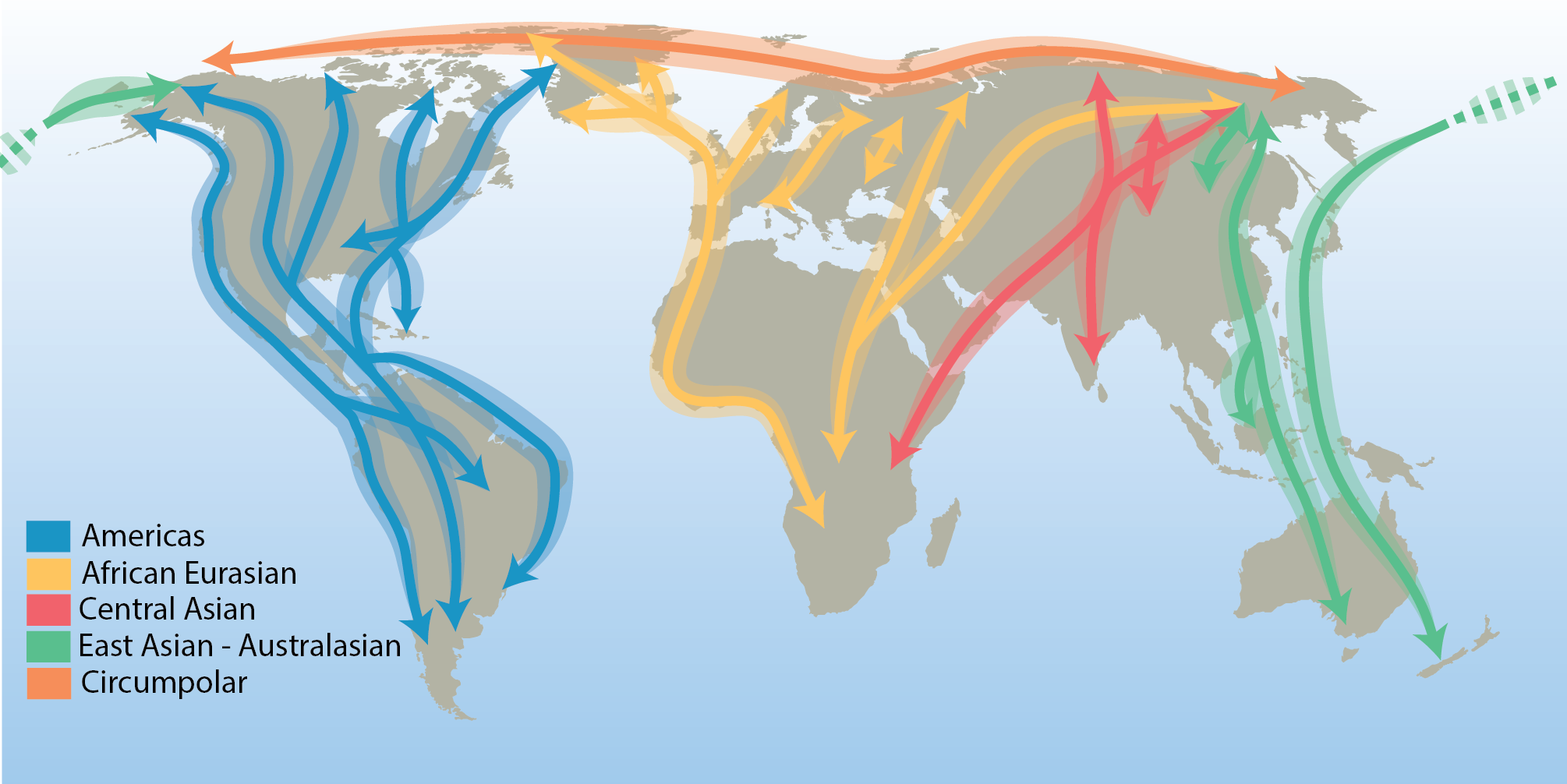

There are few true Arctic specialist birds that remain in the Arctic throughout their annual cycle. They include the willow and rock ptarmigan (Lagopus lagopus and L. muta), gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus), snowy owl (Bubo scandiacus), Arctic redpoll (Carduelis hornemanni) and northern raven (Corvus corax)—a cosmopolitan species with resident populations in the Arctic. All other terrestrial Arctic-breeding bird species migrate to warmer regions during the northern winter, connecting the Arctic to all corners of the globe. Hence, their distributions are influenced by the routes they follow. These distinct migration routes are referred to as flyways and are defined by a combination of ecological and political boundaries and differ in spatial scale. The CBMP refers to the traditional four north–south flyways, in addition to a circumpolar flyway representing the few species that remain largely within the Arctic year-round (Figure 3-20). STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 48- Figure 3.20

-

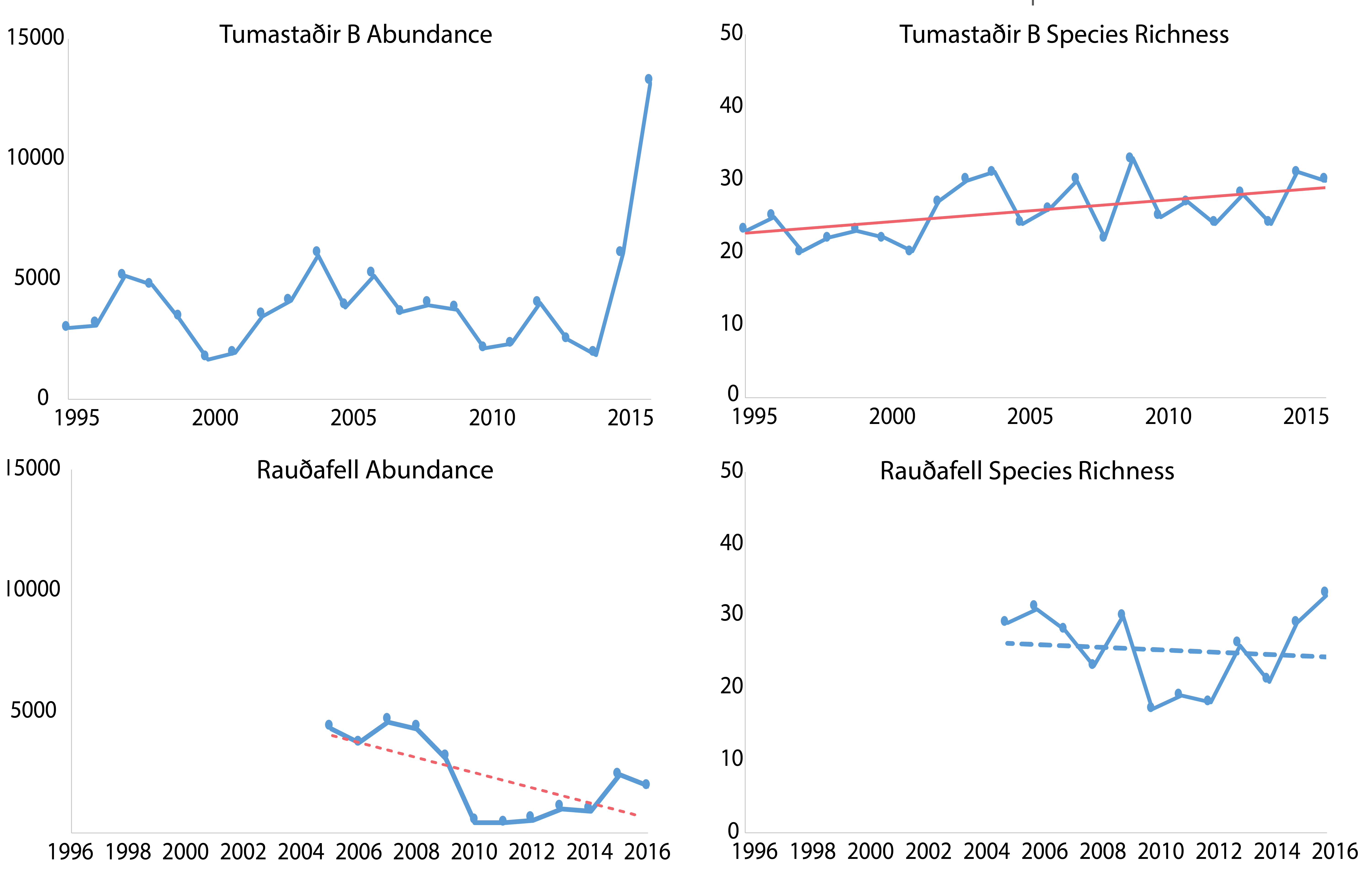

Trends in total abundance of moths and species richness, from two locations in Iceland, 1995–2016. Trends differ between locations. The solid and dashed straight lines represent linear regression lines which are significant or non-significant, respectively. Modified from Gillespie et al. 2020a. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 41 - Figure 3.14

-

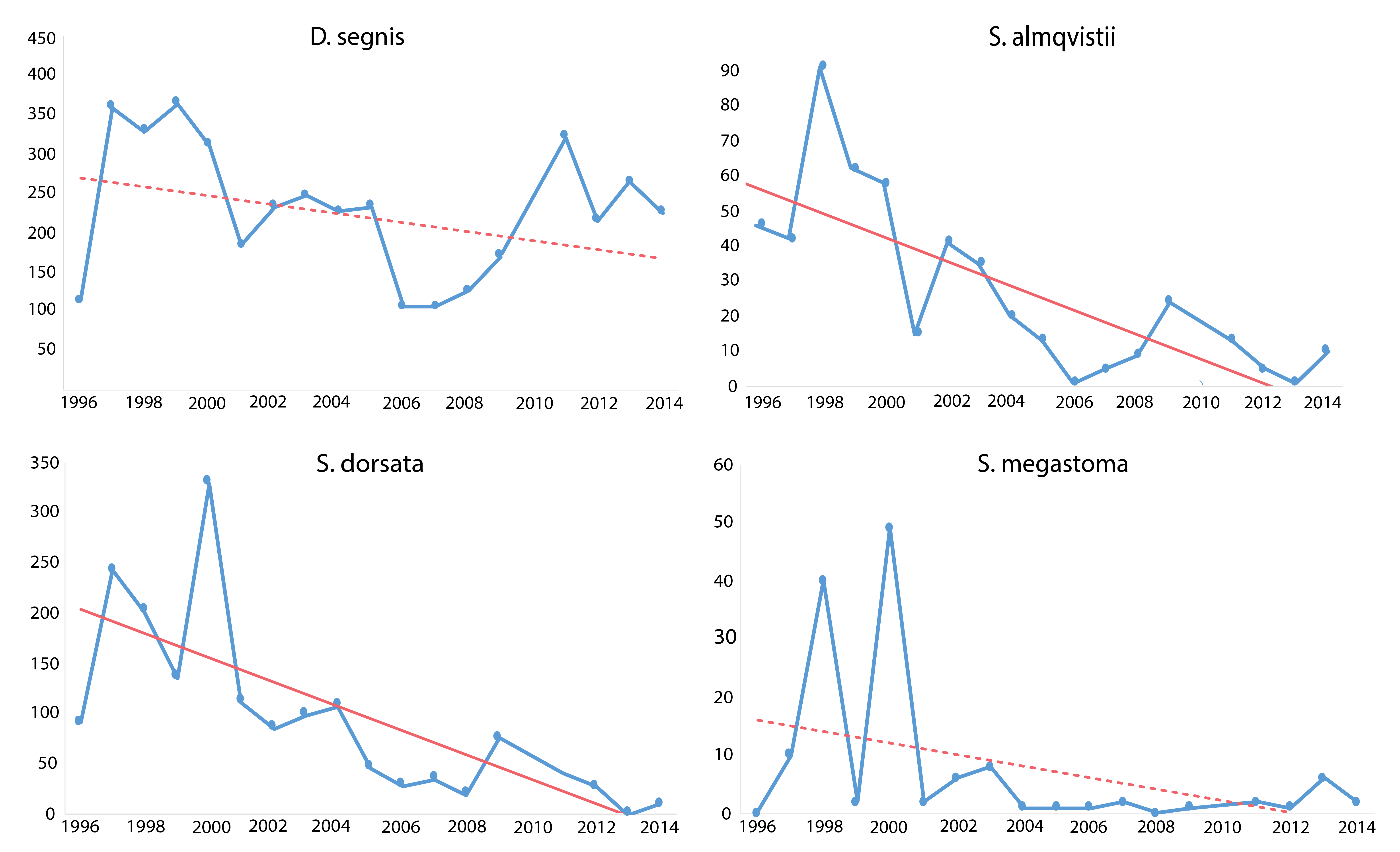

Trends in four muscid species occurring at Zackenberg Research Station, east Greenland, 1996–2014. Declines were detected in several species over five or more years. Significant regression lines drawn as solid. Non-significant as dotted lines. Modified from Gillespie et al. 2020a. (in the original figure six species showed a statistically significant decline, seven a non-significant decline and one species a non-significant rise) STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 39 - Figure 3.11

-

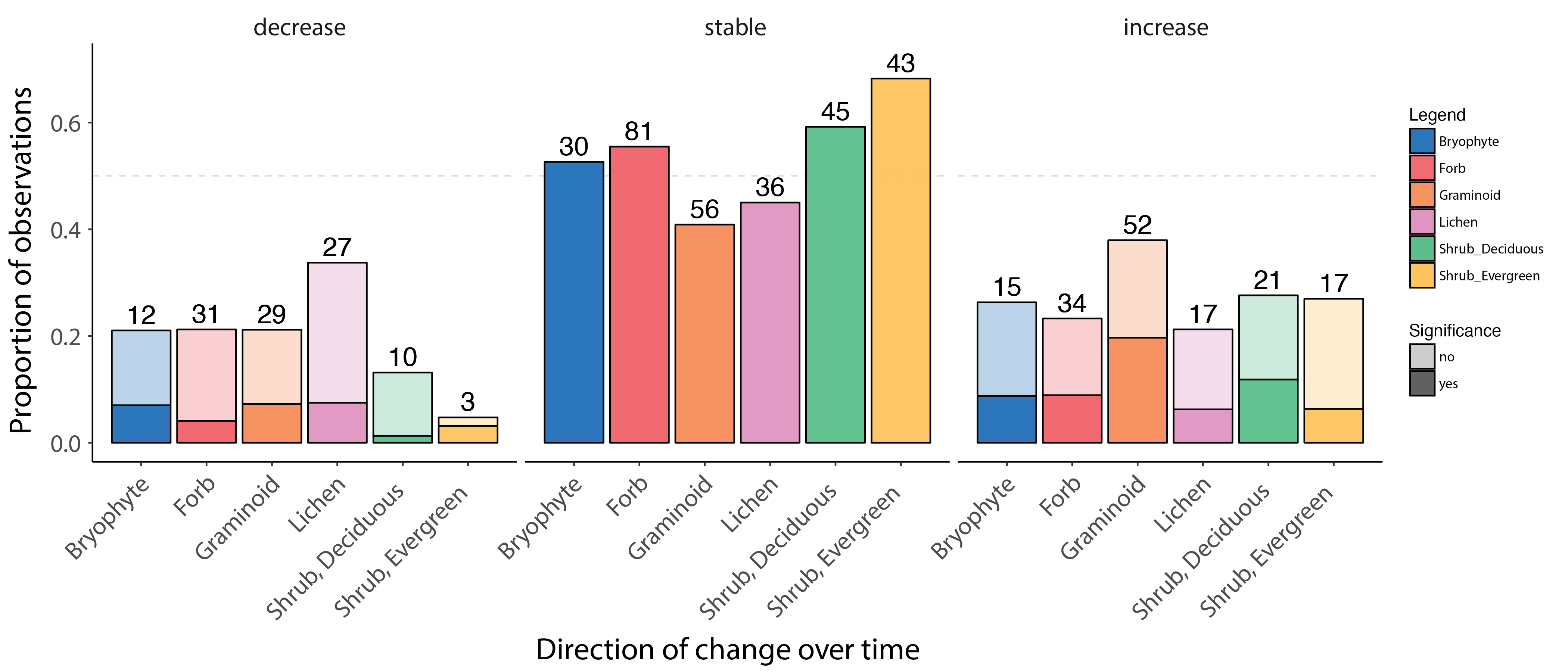

Change in forb, graminoid and shrub abundance by species or functional group over time based on local field studies across the Arctic, ranging from 5 to 43 years of duration. The bars show the proportion of observed decreasing, stable and increasing change in abundance, based on published studies. The darker portions of each bar represent a significant decrease, stable state, or increase, and lighter shading represents marginally significant change. The numbers above each bar indicate the number of observations in that group. Modified from Bjorkman et al. 2020. STATE OF THE ARCTIC TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY REPORT - Chapter 3 - Page 31- Figure 3.2

CAFF - Arctic Biodiversity Data Service (ABDS)

CAFF - Arctic Biodiversity Data Service (ABDS)